Detail of May, Folio 5 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

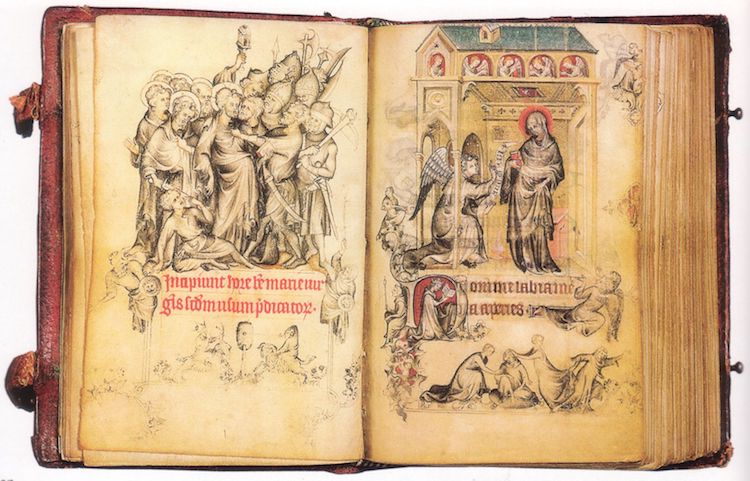

This 15th-century book of hours is among the world's most celebrated illuminated manuscripts. With sky-high levels of detail and decoration evident on every parchment page, the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry illustrates the time and talent required by the manuscript-making process, shining a light on the luminous tradition.

What is a Book of Hours?

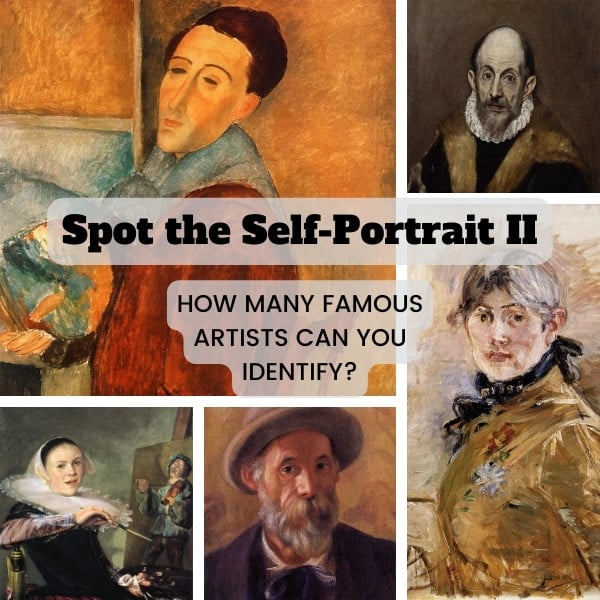

“Hours of Jeanne d'Evreux,” 1325-1328 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

By the end of the 13th century, the book of hours was the most popular type of medieval manuscript. In fact, its ownership transcended members of the clergy; it was also used by ordinary people and even bibliophilic collectors like Duke Jean I of Berry, a French nobleman celebrated for commissioning the Limbourg Brothers to create the Très Riches Heures, a particularly sparkling book of hours.

The Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry

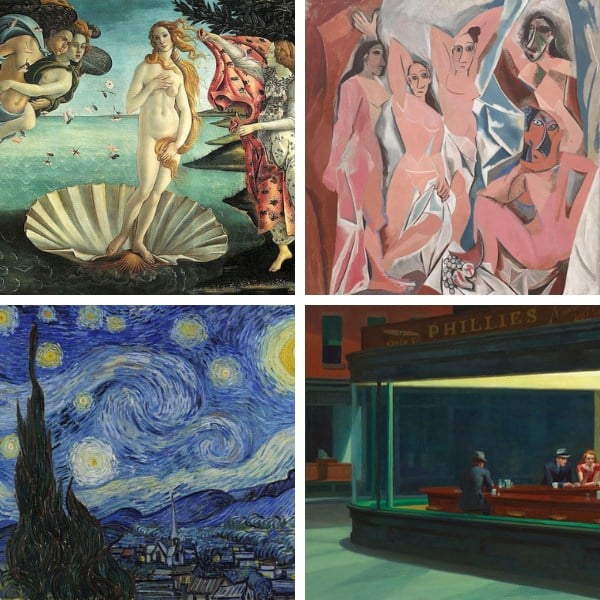

Left Photo: Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain); Right Photo: Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain)

The Très Riches Heures (“The Very Rich[ly Decorated] Hours of the Duke of Berry”) dates back to 1412. Measuring 8.5 by 12 inches, the handheld book comprises 206 calfskin parchment pages adorned with ornate calligraphy, intricate initials, opulent marginal decorations, and splendid miniatures, or small illustrations. In total, the manuscript features 131 minutely detailed miniatures, which are rendered in luxurious mineral and plant-based pigments mixed with natural gums and embellished with silver and gold leaf.

While the illustrations' grandeur is unusual for a book of hours, the content itself is typical. The first 14 folios, or pages, feature a calendar that outlines important liturgical days accompanied by (for the first time in book of hours' history) full-page miniatures. These illustrations show the Labors of the Months, a 12-scene cycle portraying seasonal, harvest-related activities. In the Très Riches Heure, these scenes star peasants and aristocrats and are set before the Louvre and other medieval castles in France. Above each miniature is an archway housing the relevant zodiac sign.

The remainder of the manuscript is made up of various holy texts—including readings from the Gospels, Prayers to the Virgin, and Psalms—as well as the hours.

Illuminating History

Detail of January, Folio 1, featuring Jean de Berry (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

ours decorated by the Limbourg Brothers for the duke.

Less than a decade later, Jean commissioned the trio to illuminate the Très Riches Heures. While the bulk of the book—including most of the calendar leaves —is attributed to the Limbourgs, the brothers (as well as the duke) died before its completion. From 1416, different painters would continue working on the miniatures. While most of these artists are unattributed, historians hypothesize that a contributor once deemed the “Master of Shadows” was Early Netherlandish illuminator Barthélemy van Eyck, while French miniaturist Jean Colombe is confirmed to have finished illustrating the book in 1489.

Luminous Legacy

Chateau de Chantilly (Photo: Stock Photos from Vaflya/Shutterstock)

Since its completion, the manuscript has changed hands several times, with owners including Margaret of Austria, a female regent, the Serras, an aristocratic Italian family, and, finally, Henri d'Orléans, Duke of Aumale, an exiled French ruler. In 1871, this nobleman brought the manuscript to his palace, the Château de Chantilly. Today, it remains in the Condé Museum, the chateau's gallery—a location that, by the turn of the 20th century, brought the book out of obscurity and into the spotlight.

Today, the Très Riches Heures is celebrated for the innovations that set it apart from other illuminated works of the time: extravagant decoration, page-sized miniatures, and prolific illustrations. Together, these splendid qualities make the manuscript an important masterpiece of Gothic art—and one of the most precious books in history.

Related Articles:

7 Medieval European Sites You Can Actually Visit Today

The Spectacular History of Mont-Saint-Michel, a Medieval Island Off the Coast of France

How the Louvre Turned From Medieval Fortress to World-Famous Museum

6 Places in Paris Where You Can Still Experience Notre-Dame’s Medieval Magic

Notre-Dame in Art: How the Medieval Cathedral Has Enchanted Artists for Centuries