Portrait of Abraham Ortelius by Peter Paul Rubens, 1633 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

Today, many of us rely on online navigation apps (like Google Maps) for directions. Thanks to technology, we can rest assured knowing that our maps are kept up to date in real time, but it wasn’t always this way. Maps have been one of the most important human inventions, but they began as more than just a navigation tool. Throughout history, people followed, created, and constantly updated maps as a way to navigate their way through the world, but maps were also used to illustrate discoveries and communicate new ideas.

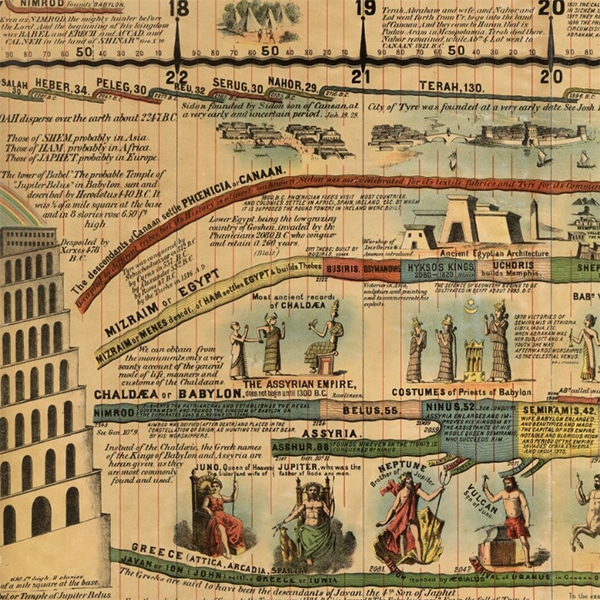

The earliest archaeological maps began as cave paintings, and slowly evolved during the Age of Discovery. During the 16th century, maps were a mixture of facts, speculation, and pure fantasy. Cartography became a celebrated art form and, today, vintage maps of the time are still sought-after collector’s items that reveal historic and unique views of the world.

Who was Abraham Ortelius?

Portrait of Abraham Ortelius in his study by Constant Aimé Marie Cap (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

Abraham Ortelius is a key figure in the history of cartography. He is known as the inventor of the atlas—a book comprising multiple maps in one format and style. Ortelius was born in Antwerp, Belgium on April 4, 1527, during the height of the humanist era. During this time, there was a revival in the study of classical antiquity, history, Greek, and philosophy across Western Europe. The 16th century was a time of exploration, revolutionary inventions, and a new view of the world.

Ortelius was fascinated by new discoveries and travel, so he began collecting books, prints, paintings, wall maps, and coins from all over Europe. During one trip to Poitiers, France, Ortelius met cartographer Gerard Mercator, who inspired him to start producing maps himself. Ortelius began his career as a map colorist for Guild of Saint Luke in Antwerp in 1547, and then became a map designer at the Plantin company in 1587. The very first maps Ortelius produced were large wall maps of the world, Egypt, the Holy Land, Asia, Spain, and the Roman Empire—and from then on, his was hooked!

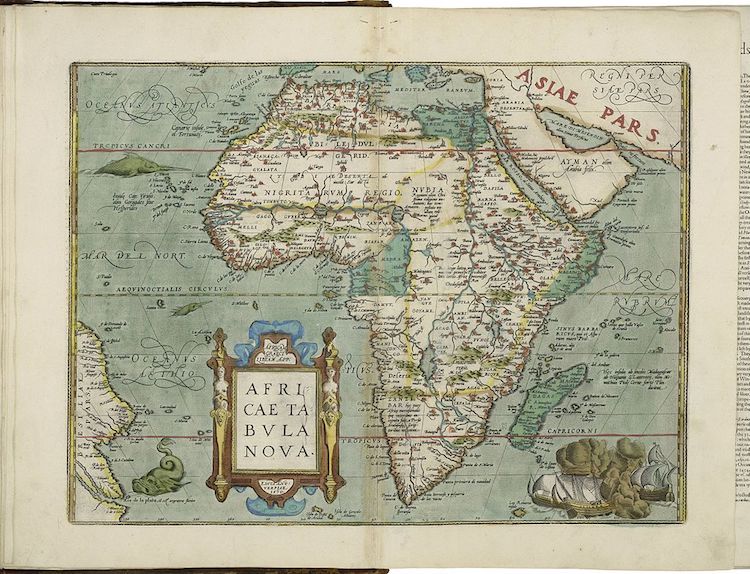

Map of Africa by Abraham Ortelius, 1608 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

The World's First Atlas

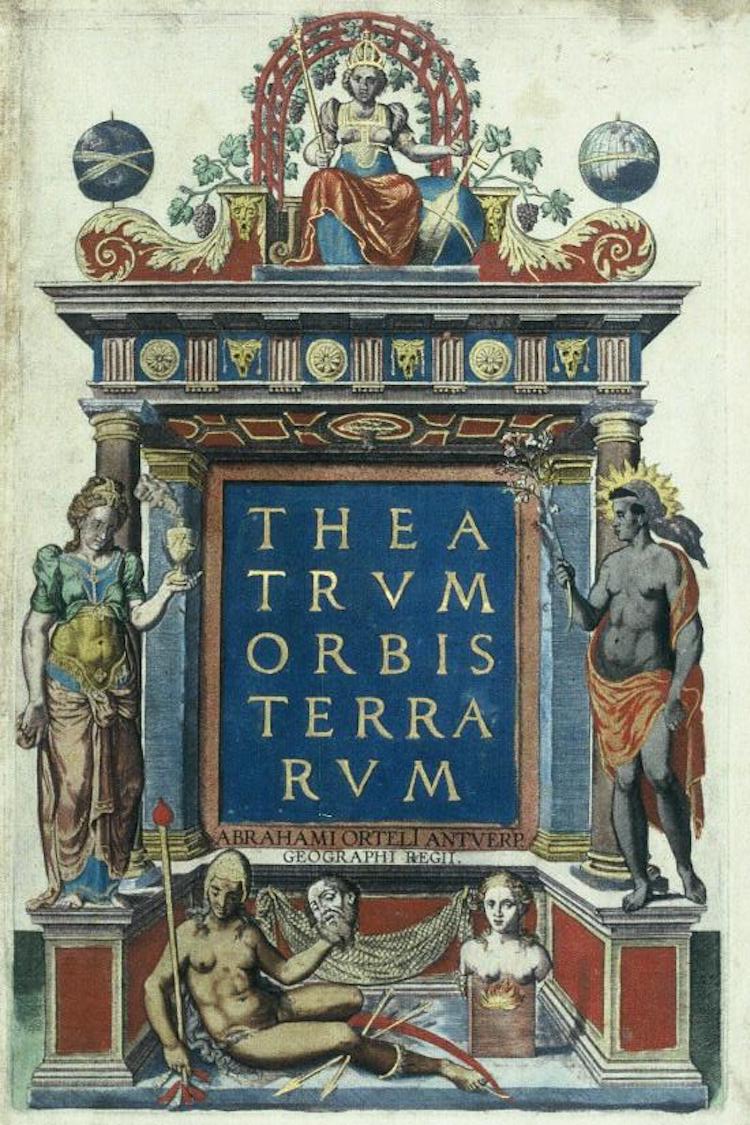

Ortelius’s first atlas was called Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (The Theater of the World). First printed in 1570, it featured a collection of 53 maps, all in the same style and size, printed from copper plates, and arranged by continent, region, and state. The atlas contained almost no maps designed by Ortelius himself, but those of other masters he admired, each with the source indicated.

Theatrum Orbis Terrarum was so successful, that it had to be re-printed 4 times in the first year of publishing. Between 1570 and 1612 the atlas was published in 42 editions in 7 languages, including Latin, English, German, Flemish, French, Spanish, and Italian.

“Theatrum Orbis Terrarum” Title-page (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

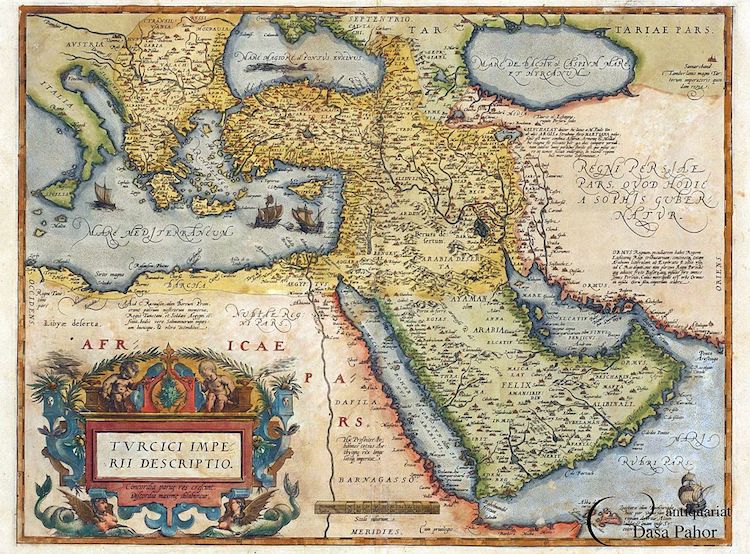

An engraved map and coloured by hand. It is part of Ortelius's Atlas “Teatrum Orbis Terarum,” Antwerp, 1570, map no. 50 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

Ortelius’ World Map

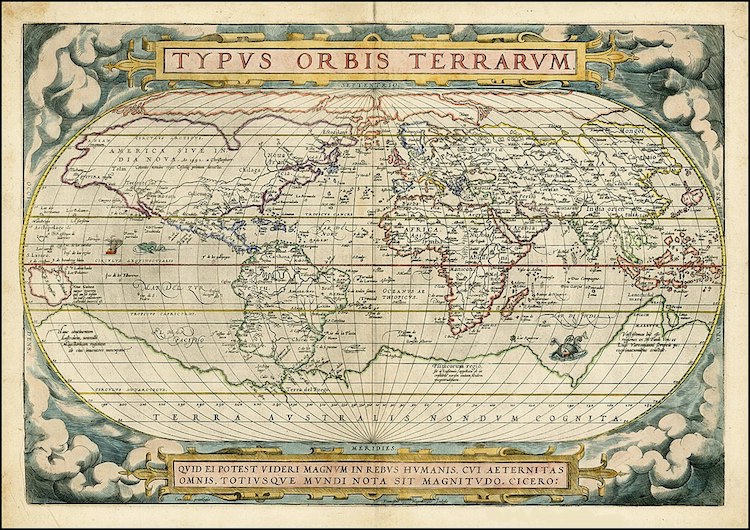

Although the Theatrum Orbis Terrarum atlas didn’t contain many of Ortelius’ maps, it did feature his most famous—Typus Orbis Terrarum (1570). Perhaps one of the most iconic maps ever made, it covers the entire world from pole to pole, revealing the shape and size of continents based on the knowledge of the time.

Ortelius designed the map according to previous world maps from other cartographers, but he also added new information based on his own guesses and estimates. At the time the map was made, much of North America was yet to be explored, so naturally, large parts of the geography are merely speculative. The eastern seaboard juts out eastward, illustrating the inaccurate measurements of longitudes at the time. It’s also interesting to note that the Mississippi River does not appear on the map, and there is no trace of the Great Lakes.

Many features on the map were also based on new information coming from explorers. For example, the coasts of South East Asia and the Indian Archipelago came as a result of the voyages by the Portuguese, and knowledge about the Asian inland was based on travel reports by Marco Polo from the 13th century.

While Ortelius' map pre-dates the official discovery of Australia in 1606, the map features an enormous mass at the base, identified as Terra Australis Nondum Cognita (Southern Land Not Known), revealing that explorers were already hypothesizing about its existence, but hadn’t quite proved it yet. The map also illustrates Papua New Guinea almost attached to the Southland, with Latin text explaining, “New Guinea, recently discovered. It is unsure whether this is an island or part of the Southern Continent.”

“Typus Orbis Terrarum” by Abraham Ortelius, 1572 edition (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

Mythical Sea Monsters

“Islandia” map by Abraham Ortelius, 1590 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

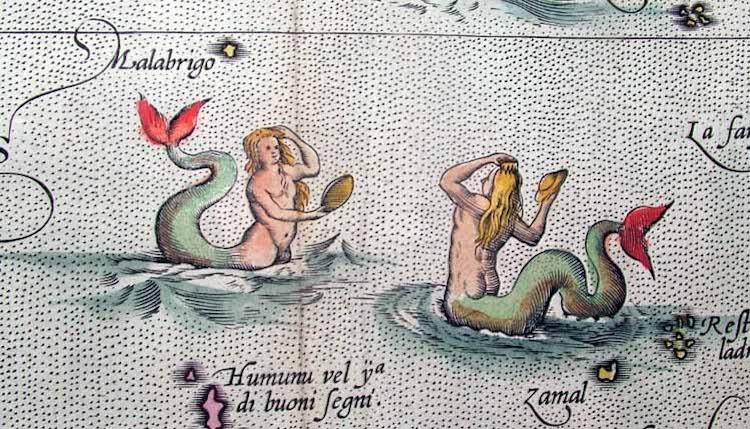

The Typus Orbis Terrarum map—and many other maps in Ortelius' atlas—feature mythical sea monsters patrolling the world’s oceans. At the time, maps that were decorated with these fantasy animals sold a lot better than those without, but they may also have been included for practical reasons.

Many cartographers of the era drew from encyclopedias, bestiaries, and biblical references, so the style of these sea creatures varied from recognizable mammals to surreal beasts. Some historians believe that they served as illustrated records of sea creature myths, while others think that they were included in maps to warn sailors of the possible dangers lurking beneath the waves.

The tradition was perhaps influenced by Greco-Roman illustrations of mythological beasts. However, Ortelius was one of the final cartographers to embrace the inclusion of them in his maps. The Theatrum Orbis Terrarum atlas was published during a time when cartographers started to prioritize science and accuracy over aesthetics. By applying both new academic standards alongside traditional illustrations of sea monsters, Ortelius embraced both sides of map making. Theatrum Orbis Terrarum therefore marks a pivotal moment in the evolution of cartography.

“Indiae Orientalis, Insularumque Adiacientium Typus,” from the “Theatrum Orbis Terrarum of Abraham Ortelius,” 1603 Latin edition (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

“Indiae Orientalis, Insularumque Adiacientium Typus,” from the “Theatrum Orbis Terrarum of Abraham Ortelius,” 1603 Latin edition (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

Related Articles:

Incredible Online Archive Lets You Download Hundreds of Ancient Maps for Free

Atlas of Literary Maps Illustrates the Imaginary Worlds of Beloved Works of Fiction

19th-Century ‘Ribbon Maps’ Let You Put the Entire Mississippi River in Your Pocket

World’s Largest Early World Map Stitched Together for the First Time